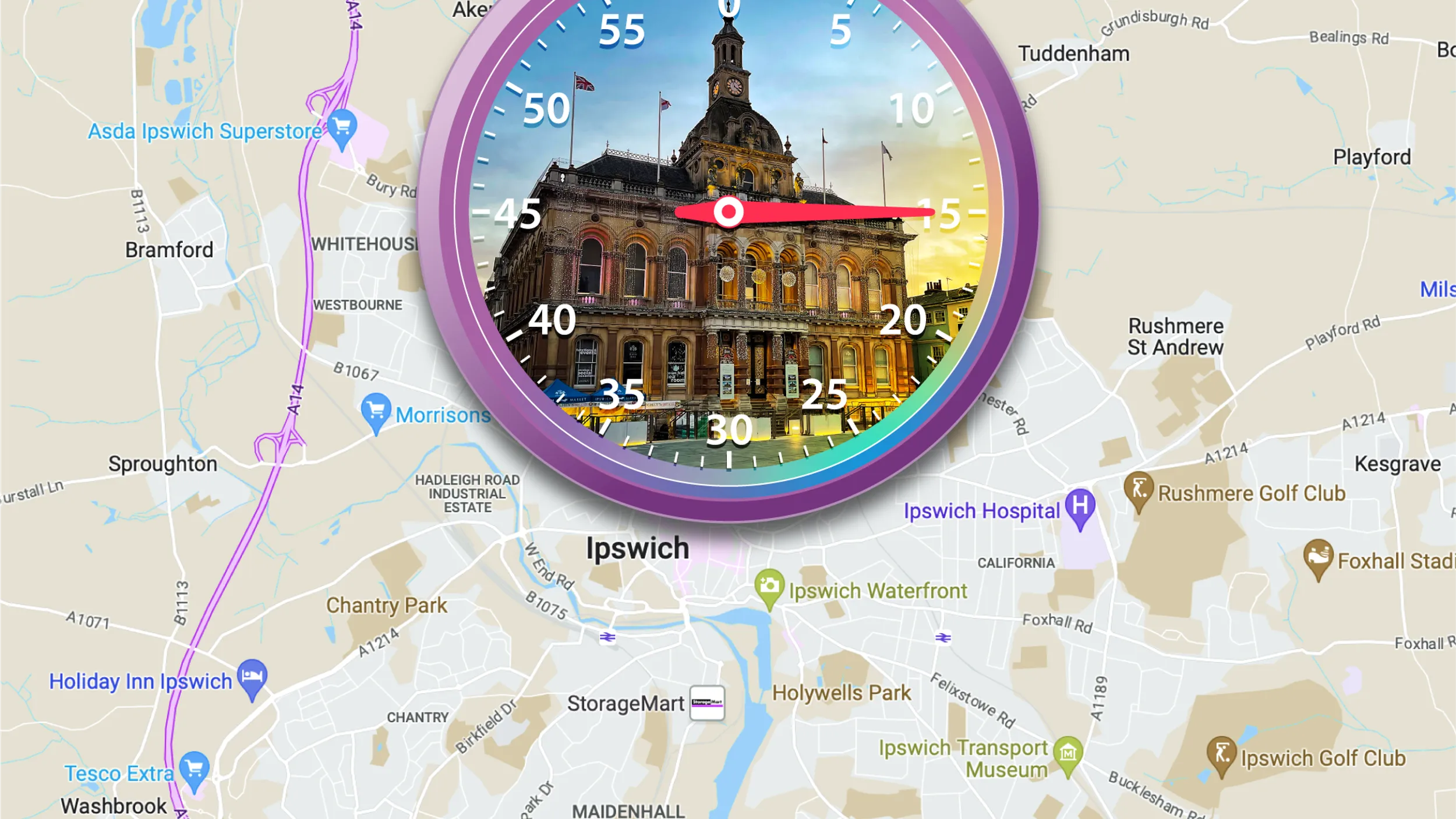

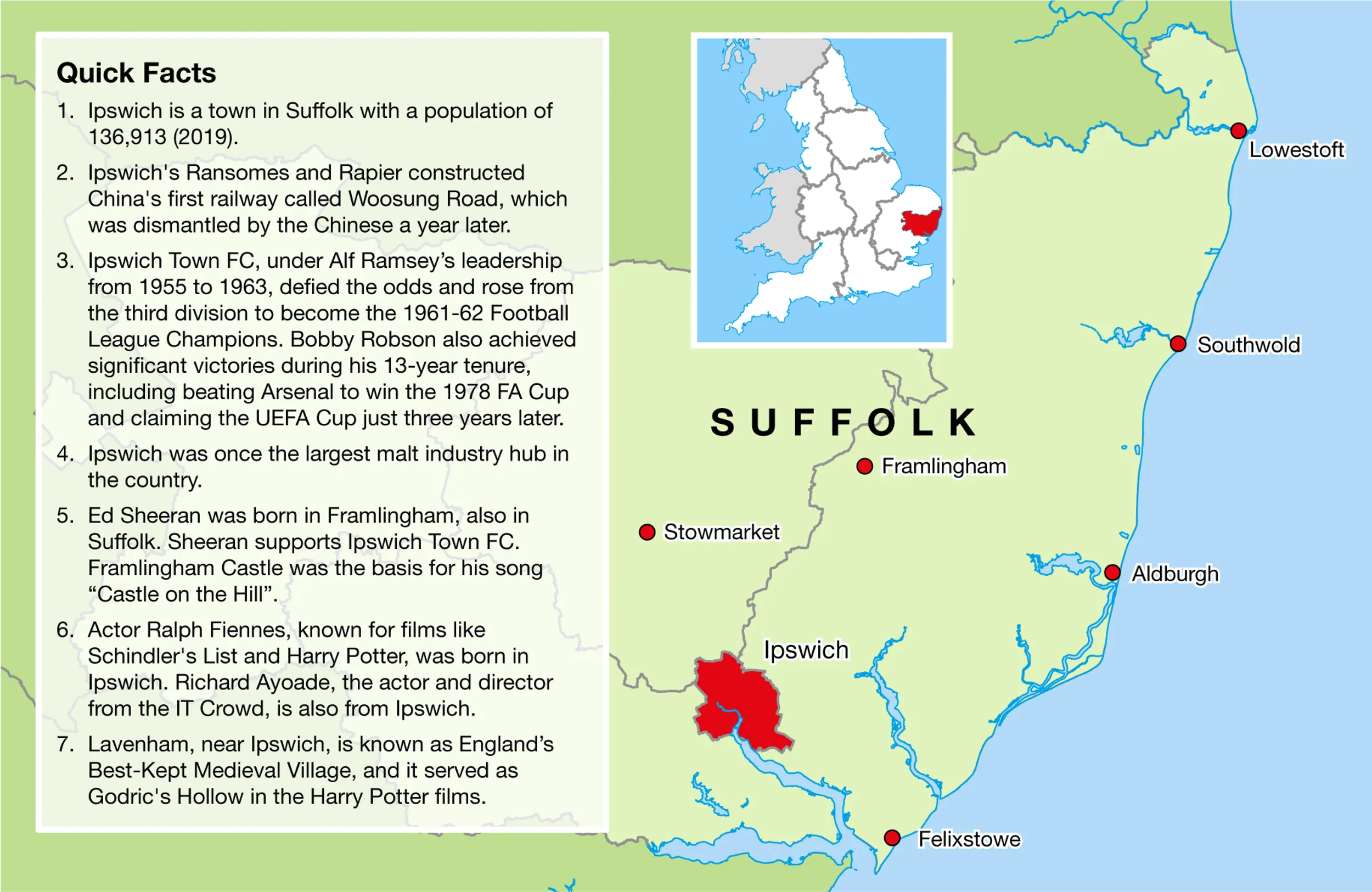

15-Minute Cities: Ipswich, the 15-Minute Town

Ipswich has recently made an exciting announcement: it is set to become the UK's first "15-minute town." But what exactly does this mean, and can it bring about an improvement over the existing urban landscape? Will the concept of the 15-minute city contribute to the creation of more sustainable urban centres?

It's high time we adopt a radical approach to reshape the way our towns function.

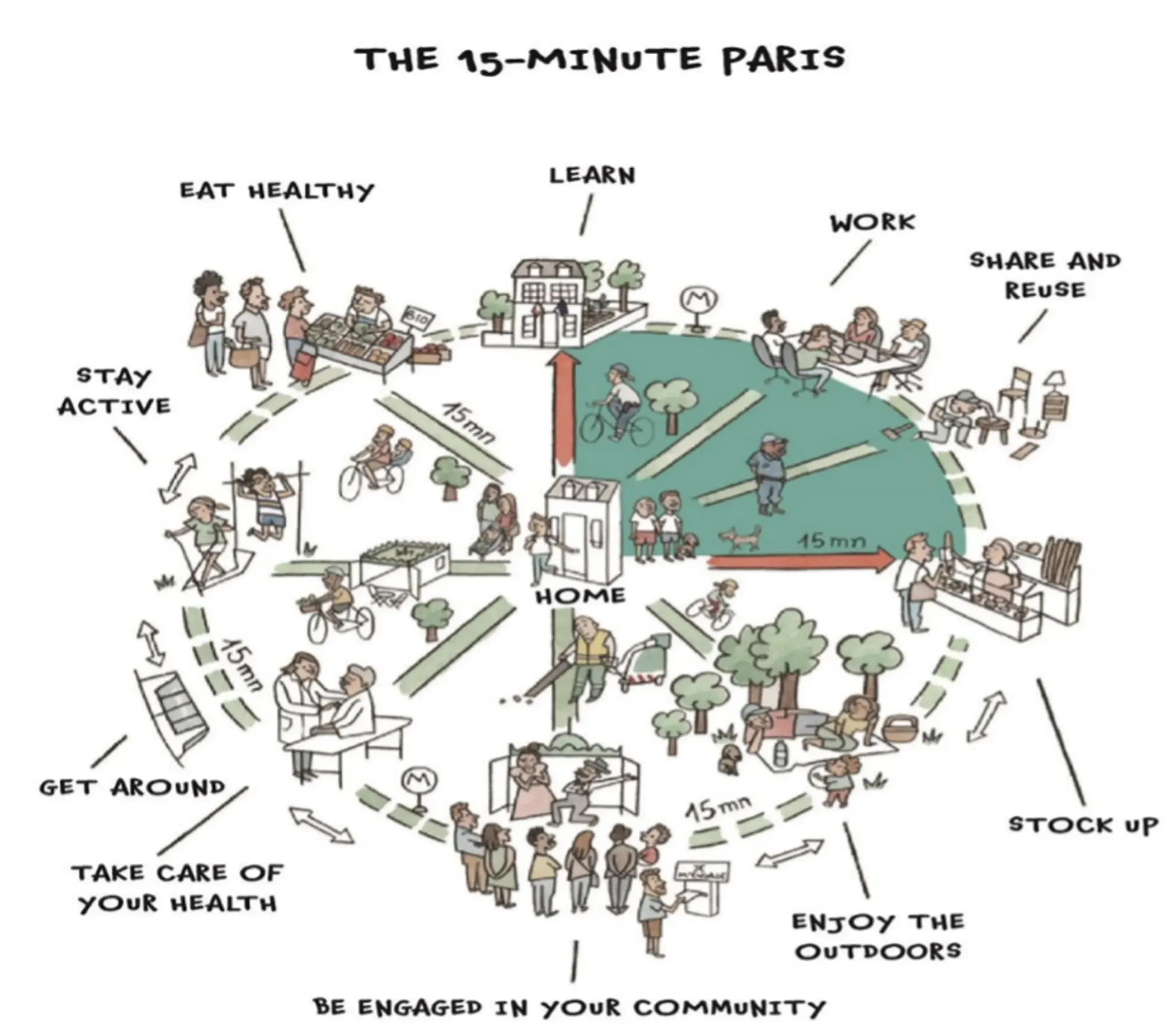

The concept of a "15-minute city" was first coined by Professor Carlos Moreno of Pantheon Sorbonne University in Paris. At the core of the 15-minute city concept is the idea that every city resident should have convenient access to essential urban services. Everyone should be able to reach their destinations within a 15-minute walk or bike ride: work, shopping, entertainment, leisure facilities, and public services.

Many of our town centres are turning into concrete deserts as shops and offices lie vacant. The pandemic has abruptly changed how we utilise street space, and as towns and cities gradually reopen, there is a unique opportunity to reconsider the allocation of space for various purposes and the role of cars compared to other modes of transportation. This is where the concept of the 15-minute city can have a significant impact on the decisions made by policymakers and the future of our town centres.

Carlos Moreno's framework for the 15-minute city emphasises four key characteristics:

- Proximity: All the services we need should be close by.

- Diversity: Land uses should be mixed to provide a wide range of urban amenities in the vicinity.

- Density: There should be a sufficient population to support diverse businesses in a compact area.

- Ubiquity: These neighbourhoods should be so common that they are accessible and affordable to anyone who wishes to live in one.

In 2021, Ipswich published several documents outlining an ambitious plan to create their own “Connected Town Centre.”

Their vision for change stems from the realisation that they need to “turn our town around” and acknowledge that the perception of the town is not what it should be. They recognised as early as 2016 that:

- The era of the traditional retail-focused town centre is over for medium-sized towns.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the decline of traditional town centres.

- More people desire to live in town centres and have their homes closer to flexible workspaces.

- Leisure and recreational activities are replacing retail units in the town centre.

Their rationale is that urban renewal and regeneration should prioritise the needs of residents over corporate retailers. Proximity is seen as the key to revitalising urban centres, which means providing all necessary amenities locally to city centre residents and fostering a sense of civic pride and urban neighbourhood. This vision would entail a significant increase in the number of people living in the town centre, encouraging new housing developments on unused sites and the conversion of redundant buildings and vacant upper floors. It envisions a town centre where housing is inclusive and financially accessible to all social groups.

Ipswich envisions a town centre where housing is inclusive and financially accessible to all social groups.

The plan also aims to attract a wider range of complementary land uses, such as convenience stores, independent retailers, schools, music venues, and increased green areas, cycling, and walking routes. Additionally, flexible workspaces will be developed to accommodate new ways of working, leading to a greater reliance on local amenities. The focus will be on heritage, culture, and the environment.

The town centre's role will evolve to serve as a place to live for commuters to London who increasingly work from home, a destination for tourists staying locally, and a place to visit. However, it is important to note that Ipswich is currently in the early stages of this aspirational project. Implementing this vision presents numerous challenges, including the remodelling of significant areas of the town centre, attracting a diverse range of businesses, increasing residential land use, and undertaking extensive "green" initiatives. Winning over the local population, garnering public support, and gaining the backing of local politicians and businesses are among the project's major hurdles. Furthermore, the question of funding remains unanswered, along with the need to overcome various planning obstacles.

All evidence points to the fact that town centres, in their current form, are not sustainable.

This not only includes retail and employment hubs but also as places to live. Will the 15-minute town concept be any different? In many ways, the outlook is positive:

- The 15-minute town can provide an appealing living and working environment by reducing commute times, eliminating car-related air and noise pollution, and creating opportunities for new businesses to establish and thrive.

- Emphasising a dynamic mix of land uses, including retail, leisure, recreation, and services, can foster cohesive communities and improve residents' perception of their locality and neighbourhood.

- Prioritising green spaces in town and city centres enhances residents' enjoyment of urban spaces, promotes overall well-being, and creates a healthier living environment.

- Developing town centres as cultural hubs and highlighting their historical connections fosters a sense of place and enhances the quality of urban life.

In short, the 15-minute city concept has the potential to enhance the quality of life in urban areas and retain their populations. However, there are concerns about inclusivity. Will the 15-minute town primarily cater to middle and higher-income groups? Will it become a privilege for the middle class? A cautionary example is Hammarby, a revitalised inner suburb of Stockholm, Sweden, where this exact scenario unfolded (see Geography Factsheet 411 What is a Sustainable City?).

Will low-income groups be left on the outskirts?

Can we guarantee that living in these rejuvenated town centres is affordable, even in rented accommodations? Given that local authorities have little incentive or funding to build public housing, it is difficult to envision these groups gaining a foothold in the 15-minute town. While it is true that private builders include a limited amount of social housing in new developments, it is doubtful that it will be sufficient to accommodate low-income groups in town centres. As a result, these households may end up being pushed to the outskirts of towns and cities.

Overall, Ipswich should be commended for taking a radical approach to rejuvenating its town centre and prioritising people. However, it's important to recognise that each town and city is unique, and what works for Ipswich may not be applicable elsewhere. Different interpretations of Moreno's ideas may emerge. Nonetheless, this represents a step in the right direction.

You may find the following sources useful for further research:

- 15 Minute City Introducing the 15-Minute City Project

- BBC How '15-minute cities' will change the way we socialise

- Ipswich Central Ambitious Vision for the revival of Ipswich

- Ipswich Vision East Anglia’s Connected Waterfront Town Centre

- Ipswich Vision Turning Our Town Around

Find exactly what you’re looking for.

- Popular Searches

- Biology

- Chemistry

- A Level Media Studies

- Geography

- Physics

- A Level Environmental Science

Newsletter

General

Work with us

Get in touch

- © 2026 Curriculum Press

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy & Cookies

- Website MadeByShape