The Summer of 2022

By Mid-2022, the UK had experienced the driest nine-month period since 1916. The South East received just 74% of the long term average for the period November to July. Along the East coast, for example, no measurable rain had fallen since early June. Large swathes of the UK had turned yellow (see image below), and hosepipe bans were in force across the country.

The 2022 heatwave was remarkable. On 19th July reached just over 40 degrees Celsius in Lincolnshire, the highest ever recorded. Similarly, the highest ever minimum night temperature was recorded, at 25.8 degrees. As a result, heat alerts were issued and for several days, people were advised to remain indoors during the day.

It was a similar story across central and southern Europe where temperatures hovered around 41 degrees Celsius for several days. Indeed, in Portugal a temperature of 47 degrees Celsius was recorded during that period.

| British Isles Heatwaves | Peak Temperature |

|---|---|

| 2022 | 40.3°C |

| 2021 | 32.2°C |

| 2018 | 35.3°C |

| 2013 | 34.1°C |

| 1995 | 35.2°C |

| 1990 | 37.1°C |

| 1976 | 35.9°C |

Historically droughts tend to occur every ten years or so, but recently the gap between droughts has started to reduce. Looking into Met Office records the number of recorded heatwaves has been increasing decade by decade. Since 2010 the UK has experienced five, including this last one in 2022 (see the table above). This would tend to suggest yet more evidence for climate change.

Impacts: 2022

On their own droughts and heatwaves can have major impacts on public health, agriculture, the economy and ecosystems. When they occur together, as they have 4 times since 1976, and now in 2022, those impacts become severe.

1) Across Europe the summer heatwaves accounted for a spike in excess deaths. Germany and Spain were hardest hit, recording around 20,000 excess deaths between them. The UK recorded 1680 excess deaths mostly attributed to the effects of extreme heat (in the UK deaths were up 7% on a normal July).

2) Wildfires raged across Europe (image below). More than 660,000 hectares of land have been destroyed by fire between January and August 2022.

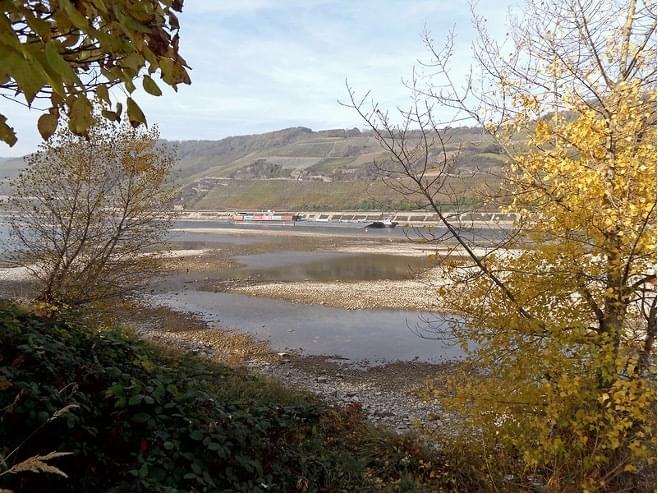

3) Shipping restrictions were introduced on major European rivers. Capacity on the Rhine was reduced to just 30% of normal tonnage as the river shrank in size (see image below).

4) Some canals have been closed in the UK.

5) Reservoirs have shrunk (see image below).

6) HEP generation across Europe has been reduced by around 20%.

7) Multiple water-use restrictions have been put in place in the UK and across Europe.

8) Crop yields across Europe are expected to be well below average.

Heatwaves, Split Jets, and Heat Domes

Recent research published in Nature finds that both the frequency and cumulative intensity of heatwaves show a higher rate of increase in Europe compared to the rest of the mid-latitudes.

In particular, heatwave days show a mean increase over Europe of +0.61 days/decade, constituting a 3 times faster rate for Europe.

This accelerated increase for Europe is even more pronounced when looking at heatwave cumulative intensity, which shows a 4 times larger trend compared to the rest of the midlatitudes.

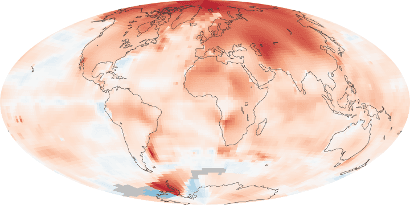

Accelerated high-latitude land warming during the summer, can be attributed to anthropogenic climate change.

So, the question becomes, what is the cause, and is this something that is here to stay?

The standard response is that we have a blocking anticyclone sitting over North-West Europe, creating a “heat dome”, and this is the cause. However, that begs the question of why the anticyclone is there in the first place?

The research published in “Nature” has come up with the answer. Essentially it finds that the upward trend in the persistence of double jet events explains almost all of the accelerated heatwave trend in western Europe.

The Polar jet stream splits into two.

The upper atmosphere winds trapped between the two streams are relatively weak and show a tendency to subside creating the blocking anticyclone (their favoured cause).

OR

The development of blocking anticyclones causes the Polar Jet to split.

“Either way, the existence of a double jet in the troposphere is characterised by a very confined subtropical jet that can affect Rossby waves in the mid-latitudes favouring the stagnation (sticking in one place) of ridges and troughs along the Rossby waves and thus keeping the anticyclone stuck in one place.”

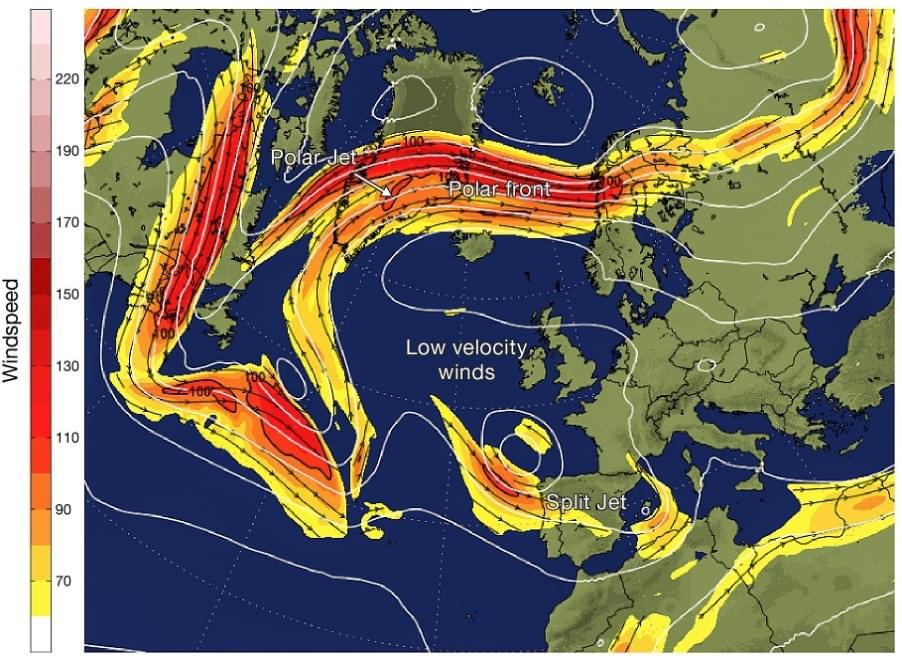

This map represents the pattern of wind flow high up in the atmosphere. The white lines are isobars at the 500mb level. Notice the clustering of the isobars along the polar front and how that affects upper atmosphere wind speeds. The Jet stream is indicated by the darker colouring. The split in the jet stream can be clearly seen with two flows:

A strong jet over the North Atlantic, Northern Scandinavia and Eurasia.

A secondary jet stretching down through the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa.

Between the two jets and sitting almost directly above the British Isles, there are almost no isobars at the 500mb level. This is associated with stagnant upper atmosphere winds, subsiding air, and the development of anticyclonic conditions at the surface.

Possible causes?

The authors of the research suggest that a possible driver can be found in the increased thermal contrast across the Arctic coastline (arctic amplification). They argue that as climate changes the land masses around the Arctic are warming up each Spring much faster than the Arctic Ocean.

So, over land the poleward temperature and pressure gradients are less than over the ocean. This in turn affects the dynamics of the Rossby wave pattern and this favours more persistent double jet flow regimes.

So, does the summer of 2022 represent the new normal for North West Europe including the UK? The short answer would seem to be yes: not only here to stay, but also likely to get worse.

Europe has seen a particularly strong increase in heat extremes since the deadly summer 2003 heatwave, which is estimated to have caused approximately 70,000 excess deaths.

This tendency is illustrated by the recent cluster of consecutive exceptionally hot and dry summers of 2018, 2019 and 2020., and now 2022.

Europe is a heatwave hotspot, exhibiting upward trends that are three-to-four times faster compared to the rest of the northern midlatitudes over the past 42 years.

According to climatologists, the 2022 heatwave was a 1 in 1,000 year event. If so, then it has to be linked to climate change. They argue that climate change has raised the summer maximum by 4 degrees, making heatwaves, such as the July heatwave of 2022, 10 times more likely.

Summer drought is likely to become more frequent. In a talk to the Royal Society in October 2021 Sir James Bevan, CEO of the Environment Agency, painted a sobering picture of a future of hotter drier summers and less predictable rainfall. He predicted that the events of 2022 are likely to become more commonplace as a result of human induced climate change:

Summer rainfall is expected to decrease by approximately 15% by the 2050s in England.

The south-east we will increasingly see temperatures above 35°C, and sometimes 40°C.

By 2050 the amount of water available in England could be reduced by up to 15%; that some rivers will have up to 80% less water in summer.

Mitigation or Adaptation?

It seems that the changes we can see occurring cannot be stopped or even mitigated in the short and medium terms. Options are limited and boil down to two sets of strategies:

Limit the increase in the rate of global warming by moving away from fossil fuels in order to mitigate the impact of climate change. Even if that happens, however, any reduction in then level of greenhouse gases will take time to impact on global warming.

Develop strategies to adapt to the new normal. The problem here is that we don’t yet know what that new normal looks like. Further, the UK has little experience of dealing with and adapting to extreme temperatures. That leaves a large question mark over our ability to adapt leaving sections of the UK population, and economy particularly vulnerable, until those strategies are developed.

by Phil Brighty

Further Reading

Accelerated western European heatwave trends linked to more-persistent double jets over Eurasia, Efi Rousi Kai Kornhuber , Goratz Beobide-Arsuaga, Fei Luo & Dim Coumou July 2022, Nature

Why does the weather stall? New theories explain enigmatic ‘blocks' in the jet stream; Paul Voosen in Science, March 2022

Articles and Blogs on Netweather.tv

The record breaking summer of 2022 in the UK and Europe Jo Farrow, September 2022.

Split Jet Stream Leaves The Weather Stuck In A Rut, Terry Scoley, June 2018.

Find exactly what you’re looking for.

- Popular Searches

- Biology

- Chemistry

- A Level Media Studies

- Geography

- Physics

- A Level Environmental Science

Newsletter

General

Work with us

Get in touch

- © 2026 Curriculum Press

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy & Cookies

- Website MadeByShape