Gentrification: Progress, but Who Is It For?

Urban regeneration is a long-established process that has seen parts of our larger cities undergo major change over the last 50 years or so (check out Cameron Dunn’s excellent review in Geography Factsheet 472). One outcome of the regeneration process is the “gentrification” of some parts of the inner city.

Gentrification: A process in which a poor area (as of a city) experiences an influx of middle-class or wealthy people who renovate and rebuild homes and businesses and which often results in an increase in property values and the displacement of earlier, usually poorer residents (Merriam-Webster dictionary).

It’s generally assumed that the gentrification of parts of our cities has had a positive impact on what were previously run-down and semi-derelict areas. However, not everyone agrees.

In the late '80s and '90s, public money was used via the development corporations and later City Challenge to help regenerate inner-city areas. Derelict land was cleared, canals and waterways cleaned up, public transport was upgraded, and old worn-out industrial buildings were refurbished and converted to residential uses while often retaining their original historic character.

As a result, the newly restored inner-city areas became attractive for commercial, retail, and leisure uses, as witnessed by the spectacular rise of Canary Wharf in London’s docklands, the redevelopment of the Olympic Park in East London, and more recently, the King's Cross development in London (see below) and the Curzon Street regeneration in Birmingham.

The King's Cross development

Argent LLP

To get a perspective on how much the new development has changed the area, check out London’s King's Cross Reborn on YouTube.

These restored and modernised inner city areas also became increasingly attractive places to live, particularly for young middle-class professionals. In Manchester, for example, there was a boom in new apartment building and warehouse rehabilitation (see below) which saw the population of three inner-city wards rise from around 11,000 in 2001 to over 40,000 by 2021 (City Population).

Warehouses transformed into upmarket apartments in Ancoats

Julie Twist properties

More recently, we have seen the rise of private commercial regeneration (see Cameron Dunn’s Factsheet), for example, King's Cross scheme and Liverpool One which are privately funded and solely for profit with the aim of attracting higher income groups into an area.

Has Gentrification Damaged Our Inner Cities?

Some commentators think so. A recent article in The Guardian has suggested that the process of gentrification has indeed had a damaging impact on parts of our inner cities, an impact that needs to be addressed. Their argument runs like this:

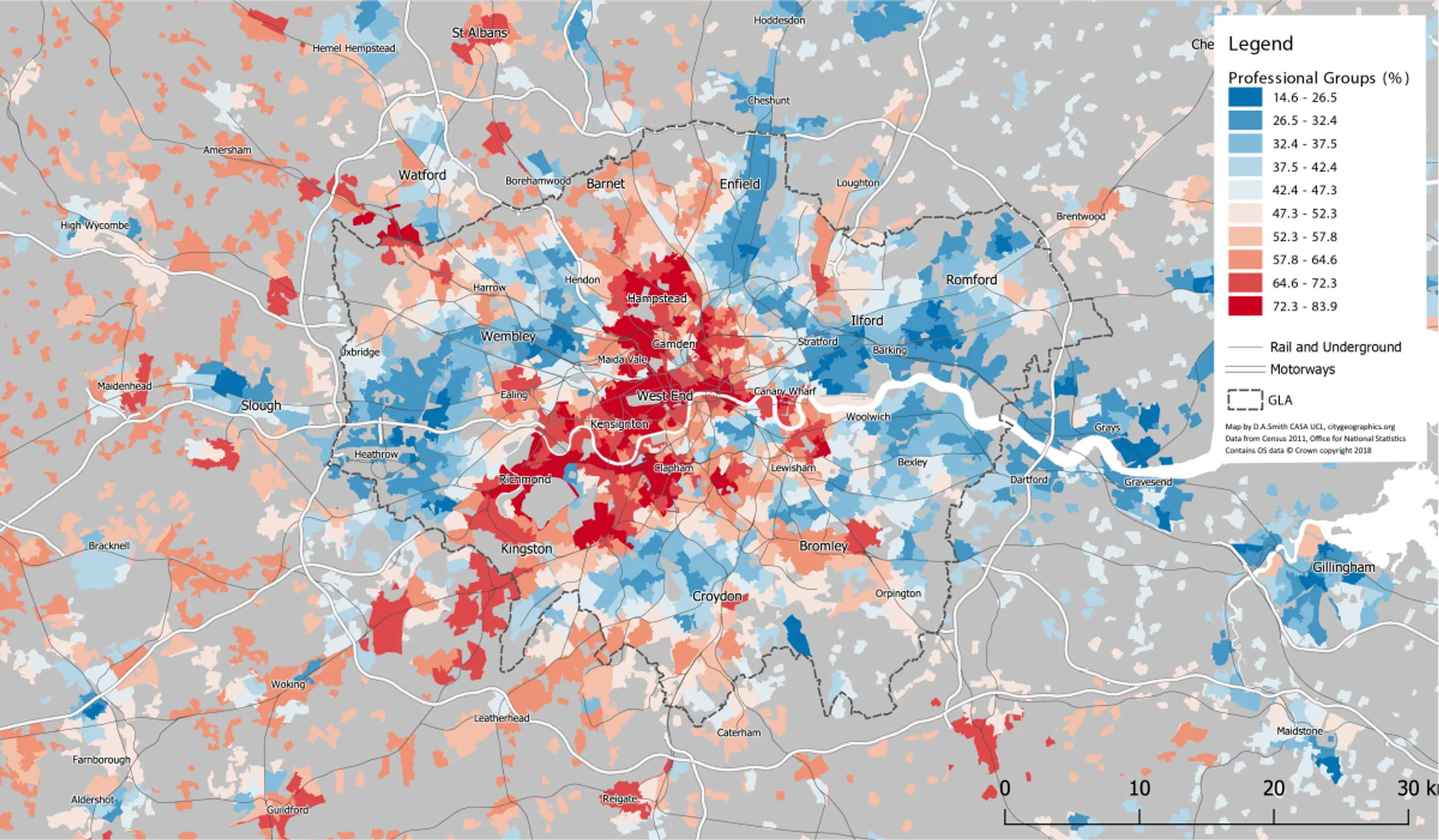

1) Certain areas within cities have proven to be more attractive as places to live for younger middle-class professionals, and as a result, areas have emerged as clusters of gentrification (see below): “... in Inner and West London, with radial corridors extending Southwest and Northwest through historic wealthy areas such as Richmond and Hampstead” (City Geographics).

Clustering of professional classes in London

City Geographics

2) The newly gentrified areas have undergone profound socio-economic change which has had a major impact on the low-income populations living there. A new group of affluent middle-class professionals have moved in with different tastes and aspirations. With them have come the bars, cafes, boutique cinemas, comedy clubs, independent and upmarket shops, and food stores which have completely transformed areas like Shoreditch in London.

3) This change has come at a cost to the locals who have lost out in a number of ways:

- Their home area has lost its original identity. Locals no longer feel that they belong.

- The new services reflect a lifestyle that the original residents neither want nor can afford.

- The increased attraction of inner-city living has driven up housing costs both for rent and purchase.

This is particularly well illustrated in a recent article in The Metro newspaper. It is well worth a read.

The gentrification of Brixton

Alamy

“When you go to the areas where there are new restaurants, people look shocked to see a black person. So I end up feeling unwelcome in my own neighborhood.”

4) As a result, many of the original residents are squeezed out. Some lucky homeowners have been able to cash in on the inflated value of their properties and move away to the suburbs. However, the most disadvantaged in these areas tend to be renters, who find themselves confronted with rapidly rising housing costs and have simply been forced out of the gentrified parts of the inner city.

The article goes on to suggest that:

5) This has led to a general outward movement of lower-income groups, either into other parts of the city or into the suburbs. What is left in the city is “areas that are close together but with a massive difference in wealth creation, housing quality, and skills levels” (Professor Patrick Diamond QMC and former Head of Policy Planning in Downing Street).

6) Often, those who are pushed out by gentrification end up far from the center, where property is cheap but jobs are sparse and commute times to the urban center are high, especially for those who cannot afford a car and rely on public transport.

7) As a result, where once the poorest residents were previously those trapped in poor, inner-city neighborhoods, they are increasingly those trapped in low-density areas on the periphery of cities.

8) Instead of being close to their work, the displaced suburban poor, often in relatively low-paid occupations, now have to commute back into the city with the additional high cost of public transport.

9) The result is that gentrification as a process has promoted increasing inequality within the inner city.

While it is possible to agree with many of the conclusions reached by the article, the final four points need to be treated with some scepticism.

- While gentrification might highlight inequality and disparities in income in particular areas of the city, it has not caused inequality.

- In any case, not all newly gentrified areas were residential; for example, the Northern Quarter in Manchester.

- The assertion that the poor are pushed to the periphery really needs closer examination, and it is doubtful whether there is evidence to support this happening in the UK. In Brixton, official figures show Brixton’s borough, Lambeth, saw its Afro-Caribbean community decrease by more than a third between 1991 and 2011. However, the situation is likely to be more nuanced. Did the original population actually move away, or is it the case that their children have been unable to compete for housing with the higher-income groups moving in as property costs have risen? Is it that group which has relocated away from the area?

Gentrification: Good or Bad?

It is impossible to say whether gentrification is good or bad. It is simply one of the results of inner-city regeneration policies. However, there are winners and losers:

- The built environment is a winner, if you like. Many parts of our inner cities which were formerly run down and places to avoid are now the opposite, pleasing to the eye and home to vibrant local communities.

- Tourism is also a winner. The newly gentrified areas in our cities are attractive, not just as places to live but also as places to visit. The Castlefield district, for example, in inner Manchester and now attracts over 2 million visitors a year to the Manchester Museum of Science and Technology, the GMEX Centre, and the Bridgewater Concert Hall complex.

- The local economy is a winner, with the input of the greater spending power that the new residents bring.

- Some sections of society, young well-educated and well-paid professionals get to enjoy the benefits of the city while living close to their workplace.

The losers, as ever, are the original low-income local communities, now strangers in their own backyard. Their aspirations were for improvements to their homes, effective rent control, a clean-up of their environment, more investment in local schools, and for their communities to be supported. In some cases, as in Brixton, what they got was something completely different.

One final concern is how the increasing reliance on private commercial regeneration projects is going to play out. When the prime motive for regeneration is profit, it is difficult to see how a place can be found for the urban poor in these developments. Instead, it will create the conditions in which gentrification clusters will emerge because that is where the spending power is.

Privately funded development isn’t just shopping malls and office blocks.

“It includes city streets, parks, and open spaces. These spaces often feel like any other parts of cities, but, in fact, they are private land.” Cameron Dunn

At what point, however, do these newly gentrified areas in privately owned public spaces (POPS) become “off-limits” to those who cannot afford to be there? As Cameron Dunn further remarks: “Currently, POPS are required by law to be open to all people, but will this always be the case?”

References & Resources

- Tracking Gentrification in London and Manchester: City Geographics

- How to reduce the damage done by gentrification: Goldin and Lee-Devlin, Guardian, June 2023

- ‘Not welcome in my own neighborhood’: How gentrification is segregating Brixton: Jordan, The Metro, October 2022

- The privatization of Urban Regeneration in the UK. Factsheet 472; Cameron Dunn

- Gentrification Causes and Consequences: Steve Holland, Journal of Lutheran Ethics 2016

Find exactly what you’re looking for.

- Popular Searches

- Biology

- Chemistry

- A Level Media Studies

- Geography

- Physics

- A Level Environmental Science

Newsletter

General

Work with us

Get in touch

- © 2026 Curriculum Press

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy & Cookies

- Website MadeByShape